The claim that “polls underestimated Trump” is so casually and confidently accepted - by both experts and the public - that it reveals something deeper and more troubling: the “experts” trusted to explain polling don’t even understand how polls work.

, , and plenty of otherwise smart people are plainly wrong about a fundamental statistical concept.Worse, their ignorance misunderstanding is suppressing statistical (and scientific) literacy around the world - and progress in the field.

The public struggles with probability concepts, and in the case of poll data, it's not an educational shortcoming, but an educator shortcoming.

Their words and analysis prove them don't understand polls, and it's not debatable.

The sentence above provokes a lot of ego-protection mechanisms (because no one likes to be called wrong - or proven wrong, in this case) but I'm not sure what else I'm supposed to say or do, because “nothing” is not an option.

And to be clear, my purpose for writing and analyzing this stuff comes from a very simple place: scientific standards.

Science is not about defending established practices, or masking insecurities regarding our qualifications or intelligence; it's about seeking the truth and improving our methods. If our definitions don't hold up in the real world, then we need better frameworks.

Yes, I understand saying that the consensus of a scientific field doesn't understand one of the most fundamental tools within it comes with a high burden of proof; it should.

But it is, frustratingly, easy to prove.

To get it out of the way:

My position is not based in semantic imprecision (though that would still be worth correcting), it is based on the fact that the field’s current consensus applies scientifically invalid reasoning.

A very small selection of quotes to start:

What Exactly Do They Mean?

“The polls missed”

“The polls underestimated”

Missed what? Underestimated what?

The “election result.” The “margin of victory.”

This is a tiny selection of what is a consensus belief among the field's experts, public commentators, and media sources alike.

Now, let me be crystal clear about what they mean when they say “underestimated” and “missed” because in 100% of cases where I have engaged with people who have written on this topic (from expert to amateur) they attempt to move the goalposts. I will not engage in semantic shell games.

They mean “the election result.”

They mean “the margin of victory.”

They mean that “margin” of the poll or poll average (e.g. Trump down by 2) should “estimate” - if accurate - the “margin” of the election result.

When that “down by 2” poll or poll average doesn't sustain (e.g. Trump wins by 2), they conclude, verbatim:

“Polls underestimated Trump.”

You can read the above sources cited, find your own, or read anything they write on the topic. It's the same misunderstanding.

Now, I cited those sources above for some names you might recognize.

But there's an easier way to hammer home the main point I want to make.

The following excerpt is from the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) committee who was put together to analyze - by experts, for experts - why the polls in 2016 were “inaccurate.”

In their own words:

“State polls had a historically bad year in terms of forecasting the state outcomes.”

Are polls supposed to forecast outcomes? State or otherwise?

Saying they had a “bad” year because they didn't “forecast” the outcomes means…if the polls were “good”…then they would have forecasted the outcomes.

There's this interesting (psychologically) but infuriating (professionally) cognitive dissonance where people CLAIM to know polls aren't predictions (they're “snapshots”)... And then after the election they say verbatim what they think the polls “predicted” and “estimated” and “forecasted.”

From the same AAPOR Report:

“the under-estimation of Trump's support (in polls of key states)…led to incorrect conclusions”

Again, comparing poll margin to election margin.

This is one of, I'm not exaggerating, dozens of the same analytical error in a report that contains less than 100 pages of content.

Another example:

“the median amount of error between the estimated and actual margin of victory across all primary contests is 9 points…

the predicted margin of victory in polls was nine points different than the official margin on Election Day.”

This is not “the media” misinterpreting something, and this is not a contextual oversimplification - the most common excuses I hear.

This panel of experts, together, in a report written by experts and for experts defined error in polls as:

“Difference between estimated and actual margin of victory”

And referred to the data in polls as providing a “predicted” margin of victory.

If you disagree that this is the consensus of the field, do not read any further. Leave me a comment about what you think the field's consensus is, with citations if possible.

This is not unique to the US. The UK, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and others are a small selection of countries from which you can find a consensus; they all believe that polls, if accurate, will predict the margin of the election result.

Without even getting into what is correct or true yet, some basic logic:

You can say that “polls are not predictions of the election result.”

You can say that polls “estimated” or “predicted” some election result.

But those statements are contradictory: both cannot be true.

If you hold both of those beliefs simultaneously, you are irrational.

If you attempt to argue in favor of both of those beliefs in a debate of fact, you are disingenuous.

If you believe they are not contradictory, you are wrong.

Yes, there are real people who - somehow - hold both of these beliefs actively in their mind.

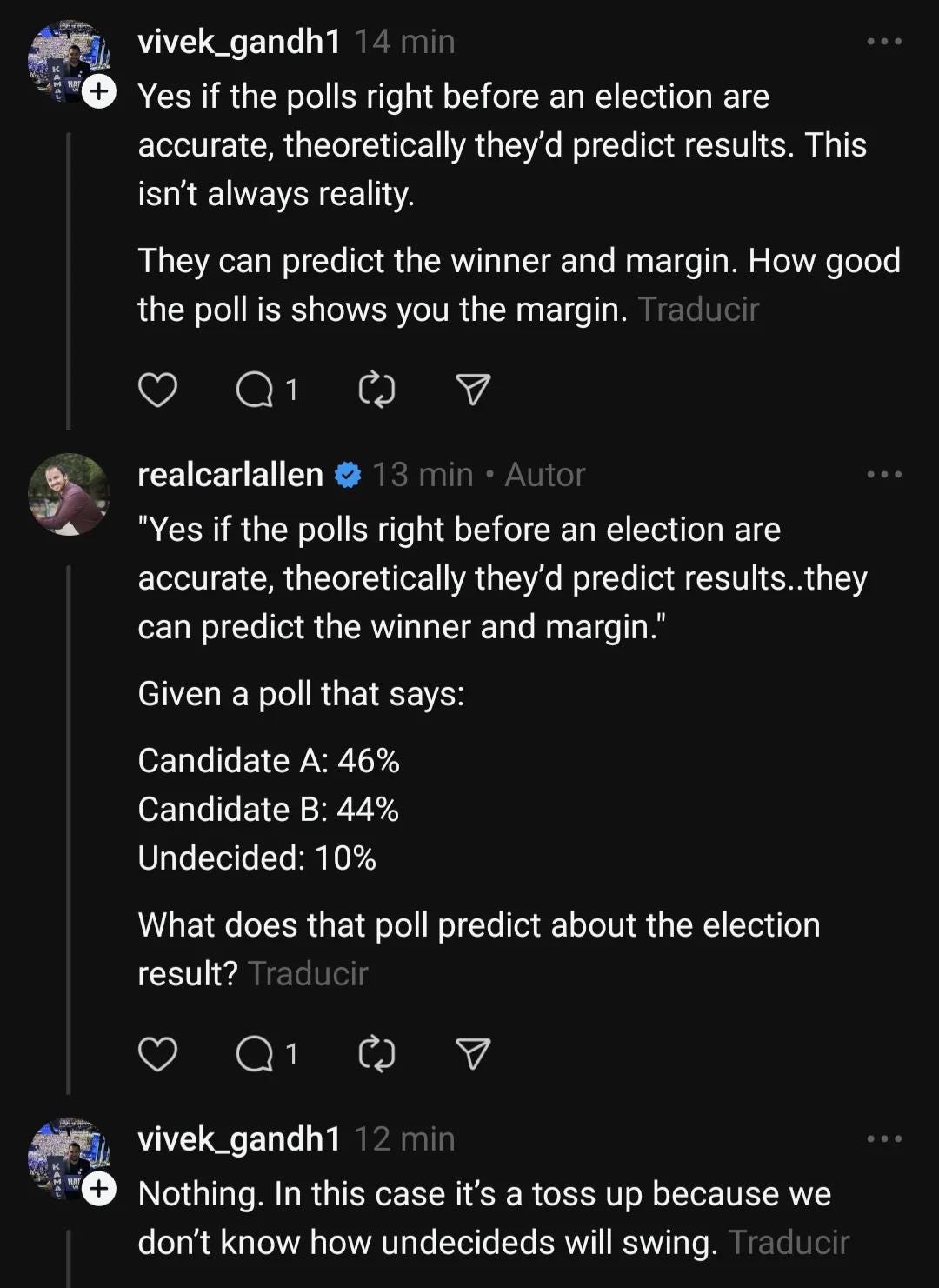

Two minutes apart. It usually takes me at least 10.

“How good a poll is shows you the margin (of the election result).”

And

Data from an actual poll from the election he referenced predicts “nothing” about the election result.

Remarkable. Intriguing. Infuriating.

I'm not sure if Vivek considers himself an expert on the topic or not - but he certainly considers himself knowledgeable enough to speak on the topic.

And proclaimed experts fare no better.

Insisting that they understand what is true (polls aren't predictions of election outcomes) while performing analysis that contradicts it is either disingenuous or simply wrong. There is no other possibility.

Hanlon's Razor suggests the latter; I'm inclined to agree with that. But pointing out that the field’s experts are either '“disingenuous or wrong” makes me look mean.

Likewise, mean ol' Marilyn proving a bunch of otherwise smart people wrong about a rather simple probability problem - does that make her analysis any more or less wrong? Debate the facts. Figure out who is right, and deal with it. Leave your petty ego aside for a change.

To sum up this section:

People, experts included, often claim to understand polls aren't predictions, but their claims of “polls predicted…” or “polls underestimated…” proves they don't.

The difference between regurgitating a definition and applying the definition to real-world examples is the difference between knowing the name for something and knowing something.

What Is The Right Answer?

Polls are NOT predictions. Polls are not estimates of election results. Polls are estimates of a simultaneous census.

This is a fact that is mathematically verifiable, and indisputable; polls are estimates of a present state, not a prediction or estimate of a future value.

Naming the term “simultaneous census” does not a invent a principle; it reveals one. One so commonly and easily misunderstood it has gone unchecked for 100 years - since the first political polls were conducted and analyzed.

With that, no one who truly understands this fact would state “the polls predicted…” or “the polls (under)estimated” some election result.

And I'll illustrate with a very simple example.

This snapshot predicts the woman in front will win.

But the woman in orange won the race. The snapshot underestimated her.

See the problem?

Because you know what a snapshot does, it's easy for you to laugh at those silly statements.

And yet, to this day, the field's foremost experts all describe the “error” of polls by how well they “predicted” the result.

For some reason, I'm the only one who currently finds a problem with this.

If I said:

“Yes, I know what a snapshot of a race does. It shows the current position of the race participants. I can use those snapshots over a period of time to inform a prediction about who will win and by how much.”

You might consider my knowledge on the topic to be acceptable. It's all reasonable enough.

But if after the race, after seeing the woman in orange won (by a rather comfortable margin!) I said:

Snapshots underestimated girl in orange. Snapshots predicted she would lose by 2 meters, but she actually won by 2 meters. Snapshots had a 4 point error.

You would raise some questions about my understanding of the thing I claimed to know. And rightly so.

Most Importantly:

Me defending my knowledge and analysis by pointing out that, pre-race, I correctly stated that “snapshots are not predictions” does not compensate for or otherwise overturn my post-race claim that “snapshot predicted girl in orange would lose by 2.”

In fact, this would be proof that I don't understand the statistical mechanics underlying snapshots!

Sometimes, people misspeak. We use imprecise words, or terms, that need correcting. Willingness to correct those words, and misunderstandings, is usually not a problem. Misspeaking is not evidence or proof of not understanding something - if you're willing to correct yourself.

But that's not the problem here. The problem in this field, right now, is a disconnect between what is true, what they know, and what they claim to know.

They use terms “underestimated” and “predicted" intentionally. From G Elliott Morris’s book:

Did Polls Underestimate Trump?

Experts claim to know “polls underestimated Trump’s performance” - but that cannot possibly be true because it is not a logically valid statement. Snapshot underestimated girl in orange.

Until this misinterpretation is fixed, the field will remain on a roller coaster of polls were good, right, bad, inaccurate, okay, great, terrible - with no ability to explain why.

Students will go uneducated, unscientific methods will go unfixed, and the standard for “best practices” will be determined by whoever “predicted” the result best.

Weight by education! We figured it out! Or not. Weight by past vote! That's the solution! Or not. Weight by online polls versus phone polls! We got it for real this time! Or not.

They can't solve the problem when they don't even ask the right question.

“Why does Mercury's orbit stop, and then reverse?” Comes to mind.

They'll find excuses, and add more epicycles and equants to defend their flawed methods, all overlooking the fact that they're working from the wrong frame of reference; they're not challenging the foundational assumption that polls, if accurate, will predict the election result.

The foundation I've proposed will correct all of it. The impact of properly defining poll accuracy will immediately yield improved methods, and new discoveries.

But that big picture analysis first requires the uncomfortable admission that the field's current consensus is wrong. Lots of retractions to published work and modifications to methods will need to be made. A lot of egos will be bruised.

But if you care about good science, this is the only path forward.

Polls didn't underestimate Trump. Because polls don't estimate anything about the election result.

If you would like a slightly more technical version of this, you can read this article. If you still crave more depth, buy the book.

Of all the races that ever were, the percentage of times a runner that the girl in orange was at that point in the race was X, would give useful information and still wouldn’t predict with 100% certainty the outcome of any given race…

Finally, someone gets this. I had nearly given up.