The field of inferential statistics is broken

But it's not the polls

The scientific state of this field is appalling. Binary thinking and internally invalid metrics have taken the place of hard-but-true probabilistic realities. It's not just the media, or online personalities…the experts are even more guilty, because they should know better. But they don't.

Avid followers might be waiting for my recap of the Australian and Canadian elections, and rest assured, I have plenty to say regarding how terribly forecasters did, again, but will try to blame the polls (which were quite good) for their own failures. I'll get to it soon.

You might consider me biased having written a book about how “The Polls Weren't Wrong” but as someone who values good science, I'd rather fix this nonsense than sell books. Although both…both is good too.

But whether or not you've read my book, I'm guessing you value statistical literacy and good science.

Let me prove to you in one short section that the existing methods for analyzing poll data is wrong.

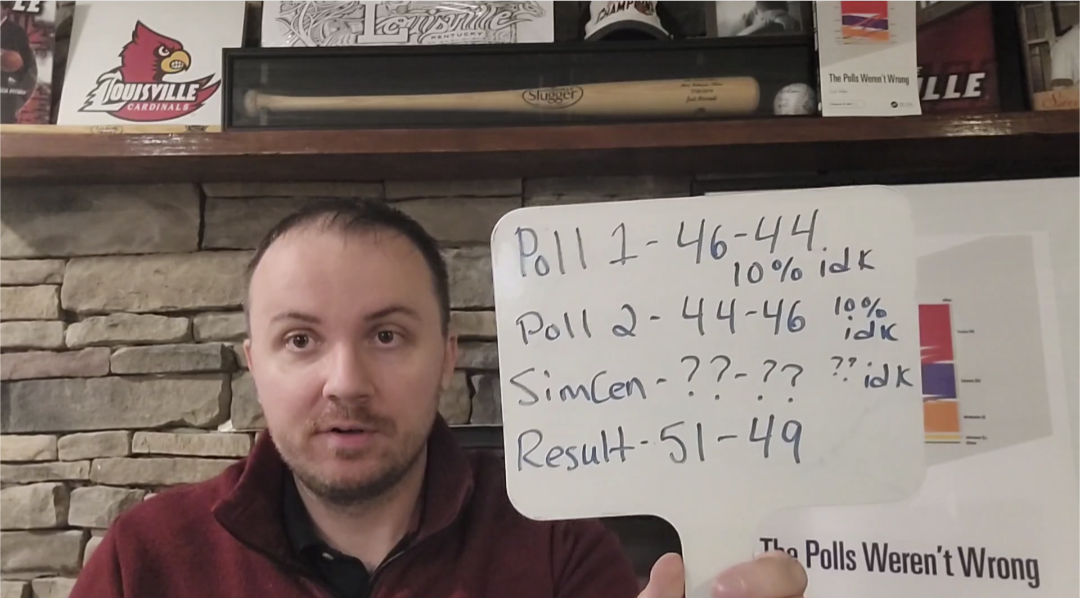

Let's assume this is a poll, or poll average, of voters in an Ohio Senate race:

Candidate A: 47%

Candidate B: 43%

Undecided: 10%

Current methods say that unless:

Candidate A wins

By 4

Then the poll was wrong, and that it had an error exactly equal to the amount candidate A didn't win by 4.

This definition, though objectively incorrect, is accepted by every statistical organization in the world that I'm aware of, including the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR).

Here is why it's wrong:

The margin of error given by a poll applies to all of the options in a poll, at the time the poll was taken, including the number who are undecided.

Clearly, the ability to plug numbers into a formula - even a relatively simple one like the margin of error formula - doesn't mean much if you don't understand what the output means.

The formula itself was originally derived from an example using an example of black and white marbles in an urn.

Cool thing about marbles: they don't change color, and can't be undecided.

That doesn't mean we can't use polls to INFORM predictions about political events involving humans, they're the best tool to do that. But INFORMING a prediction (which polls plus some assumptions plus some other data plus fancy models can help you do) is not synonymous with MAKING a prediction (which everyone from public to media to experts assert they do).

Assuming the eventual preference of those who were undecided in the poll, as current methods do, has nothing to do with the poll's accuracy.

Hell, assuming the eventual preference of those who were decided in the poll has nothing to do with the poll's accuracy!

People can change their mind for any reason or no reason. Being asked a question about who you plan to vote for today can't magically be corrected if you change your mind tomorrow.

Ignoring known confounders are only one of several issues in this field.

Without boring you with the book-level depth that come with assuming unknowns to be known, confounding variables, compounding error vs compensating error, and more, here is the math:

The error of the poll given above is equal to the difference between the poll's output and the true population at the time the poll was taken.

For Candidate A, the difference between 47% (observed) and the total percentage of voters in Ohio as qualified by the poll who would express support for that option (actual) is that option’s “poll error.”

Likewise for Candidate B and 43%

Likewise for undecided and 10%

That is, if you had asked every registered voter in Ohio the same question (in the same timeframe the poll was taken) then an ideal poll of that population would fall within the margin of error exactly as often as the confidence interval specifies.

Period. That's it. Nothing to do with the result.

In the absence of this simultaneous census standard, analysts have substituted a future value (the election result) as a very imprecise approximation.

Either out of laziness or ignorance, this imprecise approximation is not conditionally accepted as “the best we can do” it is incorrectly taught as the objective “true value”

Perfectly Accurate Polls Can Still Be “Wrong” (by this flawed standard)

In science, there is a rule:

If it disagrees with experiment or observation, then it is wrong.

The simplest example is regarding the treatment of undecided voters.

The assumption that undecideds must split evenly is poor, and unrelated to poll accuracy.

Even if a simultaneous census showed the poll to be accurate to the decimal, if undecideds split unevenly, current methods would assert the poll was wrong.

Simple arithmetic shows that undecided voters alone could tip the outcome. Is that a poll error?

The answer is no.

But current methods say yes.

That's wrong, so it needs to be fixed.

The downstream impact of fixing these basic mistakes around the calculation of poll accuracy is far more meaningful than you may think, and probably far more meaningful than I even realize at this point.

Polls are measurements, not forecasts. They are snapshots of public opinion, not crystal balls. When forecasters treat a poll as a predictor -;and use the margin of error as a line between “winning” and “losing” - they are engaging in statistical malpractice.

Worse, when the election result later diverges from what the polls “predicted,” the blame falls on the poll, not on the people who misinterpreted the polls. The credibility of polls suffers, when in truth the interpretation is at fault.

In my research, I frustratingly found that this is not new.

This Misuse Is Not Harmless, either

Misunderstanding polling leads to more than just embarrassing predictions. It has real-world effects:

It shapes media narratives and fundraising strategies.

It influences voter behavior, turnout, and perceptions of viability.

It fuels distrust in legitimate statistical tools.

More dangerously, it allows misinformation to flourish. When people are told, “The polls were wrong again,” they may conclude that all data is suspect - when, in reality, the data was misread.

The Field Needs a Correction

This misunderstanding is not a fringe critique. It is a structural error in the foundation of a field vital to science.

The public is taught to read polls by experts who don't understand them. The statistical community must take greater responsibility not only for producing accurate data, but for communicating what that data does and does not mean.

The public deserves better than an incorrect interpretation of the margin of error, and the role of polls. Polls aren't predictions. And until we start treating them that way, the field will keep making the same mistakes, being confidently and consistently wrong. Huffing about how “off” the polls were - or boasting about how “right” they were…with nothing better than Literary Digest reasoning to support their claim.

Minimal editing of this article was produced with the help of ChatGPT

I'm happily available for podcasts and speaking roles for the foreseeable future. It can be a freeform discussion, panel, seminar, or whatever interests your group.