This is something of an aside to my series on fighting misinformation, but it is, unfortunately, timely.

I'll include some charts and data that I've not seen included anywhere else (plus some that are), to help you fight misinformation - if you'd like.

Step 1 in any debate or discussion is for the people involved to state their position clearly.

Not to imply it, but to state it directly.

Many people confuse “debate” or “discussion” with “platform to say what I want to say, and for you to say what you want to say, with no enforced rules or structure”

That's not correct. Stating your thoughts, beliefs, or opinions is fine - even if those things do not correspond with reality. But those things have no place in debates or discussions of fact.

I have no interest in hearing anyone's opinions on matters of fact.

Often, when someone tries to engage on these topics, just asking them to state their position directly is too much to ask! They'll refuse, because if they state their position too clearly, they'll be forced to defend it.

I know exactly what he means here: he's implying scientific studies (regarding vaccine safety and efficacy) can be and have been manipulated “to sell their product.”

But this isn't good enough. I asked him what his position was on this, and he wouldn't give one. He wanted to talk about this topic (scientific studies on vaccines being manipulated) without being cornered into taking a position on it - thus being forced to concede when proven wrong.

No debate to be had.

(JAQing off - Just Asking Questions in the guise of skepticism or good faith - is a common tactic).

It's common: people will make a claim that seems clear enough, but once that position becomes untenable, they try to find a copout and/or move the goalposts.

When you try and make them stay on topic, or call them out for moving the goalposts, they will resort to increasingly inflammatory insults or personal attacks (even threats) to try and get you to respond accordingly: their psychological fragility so desperately wants to talk about anything other than the original topic. Even a single word that addresses the attack allows them to pretend you agreed to changing the topic. Don't even acknowledge it.

Note the only thing of any sort of substance in Tom's attempt to deflect from the topic is the only thing I responded to.

In the occasions that someone is willing to state their position clearly, we reach step 2.

Step 2: Okay, prove it.

Asking someone to state their position is important.

But making easily disproven claims that make you work hard to type a lot and provide sources to prove them wrong (only for them to say that those sources don't count, or that it doesn't address their Real Position, or my personal favorite, “whatabout this other thing?”) are among a troll's favorite things to do. And a large number of people you engage with (in person or online) will fall into this category.

For example:

“But that source is from 2010, too old to count.”

This person wants to make the debate about the relevance of data from 2010 to 2025. Nothing to do with gun homicides, safety, or anything actually on topic.

Even if you make a casual comment about how things have not changed substantially since 2010, you've let them change the topic.

Don't.

“So at least for 2010, you admit that the findings that countries with more guns had more homicide is accurate?”

No response.

In a rare bit of honesty, Brendan made the same observation about some remarkably outdated 2016-2017 data. I mean, nine years old? Who would trust that data?

Then, he quickly gives up the game: nothing I post is reliable.

Credentials, intelligence, and realness of an account does not make someone a troll (or not). Sure, fake and anonymous accounts more commonly resort to troll tactics, but that's far from the only ones that do.

Most often, disingenuous types who want to talk but not engage in any substantive debate try to shift the burden of proof, to prevent you from succeeding in Step 2. That is, they make a claim, and then demand that you prove them wrong.

Most people I engage with online won't get past here. Because most of them aren’t worth it.

I have no interest in engaging with - by definition - unreasonable people.

Step 2a, if you are reasonably sure it's not a troll:

What facts, evidence, and/or proof would change your mind?

Most often, the honest answer is: “nothing.”

The vast majority of people hold positions that they are absolutely unwilling to reconsider. I would truly have more respect for these people if they were intellectually honest and admitted as such.

During COVID, you probably remember these types saying, in order:

“well, I don't want to be the first to get vaccinated” (despite trials having been done)

“well, it's still not FDA approved”

(After FDA approval) “well, I don’t trust the data because (insert boogeyman here)”

(After vaccines are shown to be safe and effective) “well, I don't believe any of this stuff should be mandatory, I don't like the mandatory part.”

The real answer was always “there’s nothing you can say, no data you can show me, that will change my mind.”

They know that's not rational. The coping mechanism is the “most reasonable excuse” - whatever excuse (which sometimes seems reasonable) they can give to hide their true position (which is unreasonable).

It's not always conscious, either. People believe, largely, their beliefs are rational, even if they aren’t. There are a long list of rhetorical techniques (conscious and subconscious) employed in a remarkably predictable manner by people who hold such intractable beliefs.

I will post about many of them, how to identify them, and counter them, in my misinformation series.

But intellectual honesty is hard, and it's not always their (conscious) fault. There are a plethora of psychological reasons: ego-protection, in-group loyalty, cognitive dissonance avoidance, motivated reasoning, many more - that allow people to hold irrational beliefs but feel as though they’re rational.

The “backfire effect” in which people hold their positions MORE STRONGLY after being shown it's factually incorrect is one of the most interesting human traits, in my opinion.

People often double down on beliefs that have been disproven not because they're malicious, but because changing them threatens their identity and self-worth.

There are few (if any) issues where this distinction is more clear than guns.

Nonetheless, if someone is willing to state their position clearly (e.g., the number of guns doesn’t matter) and also that they're willing to be proven wrong, it's okay to engage.

Just don't expect it to accomplish much.

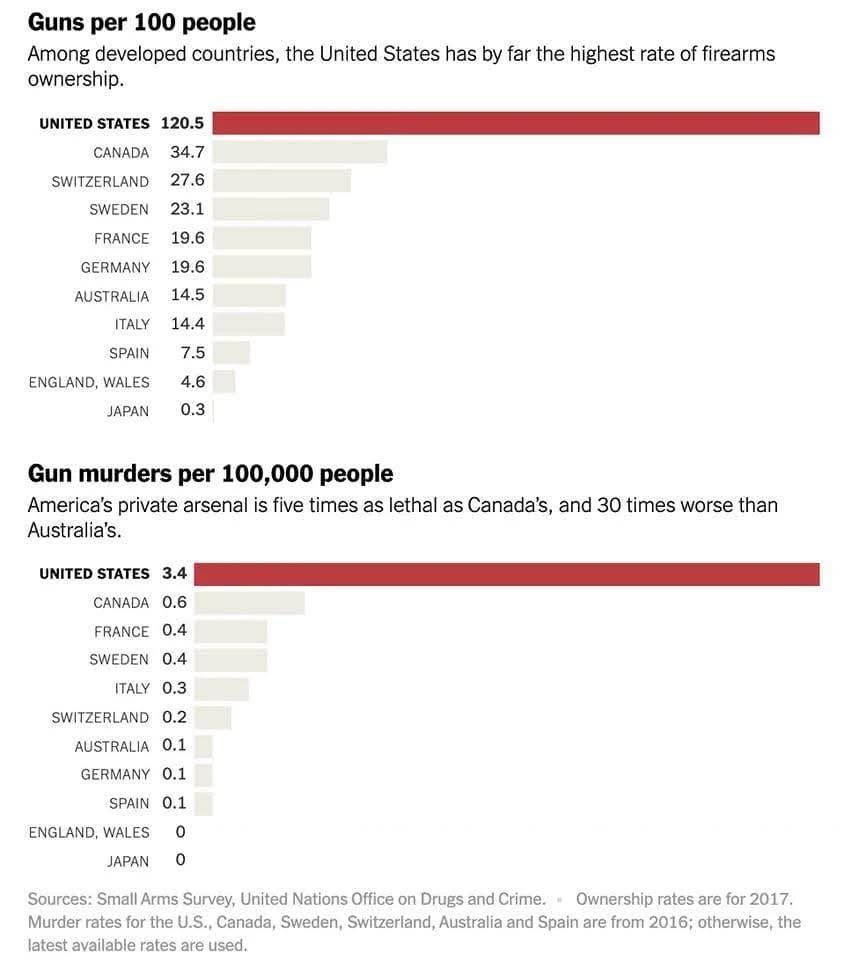

Recently, I presented this chart.

Many of the responses were to the predictable effect of:

“But the US has more people…but the US has bigger cities…but the US has more diversity”

To these people, all of these better explained the homicide rate in the US than the fact that it has more guns.

One individual claimed all three of these things. He wasn't trying to make a logical appeal, he was taking the, uh, shotgun approach to argumentation. Make a bunch of claims and hope something hits.

These variables are certainly possible confounders: more people in a smaller area, with more diversity of beliefs/backgrounds, might yield more violence.

No problem.

So I asked: if I give you data to account for all of this, and it's still clear the US has far higher homicide rates, will you admit it's the guns?

Yes or no?

(Note, lots of people at this stage - again because they're trying to protect themselves psychologically - will do anything to avoid being cornered into admitting they're wrong.) For example:

Will actively avoids a simple “yes” or “no” question (will you admit you're wrong if proven wrong?) first by saying he'd “love” to see it, then by pretending he's making some sort of challenge.

No.

Until they agree to admit they're wrong if proven wrong, they're not agreeing to the terms of a rational discussion.

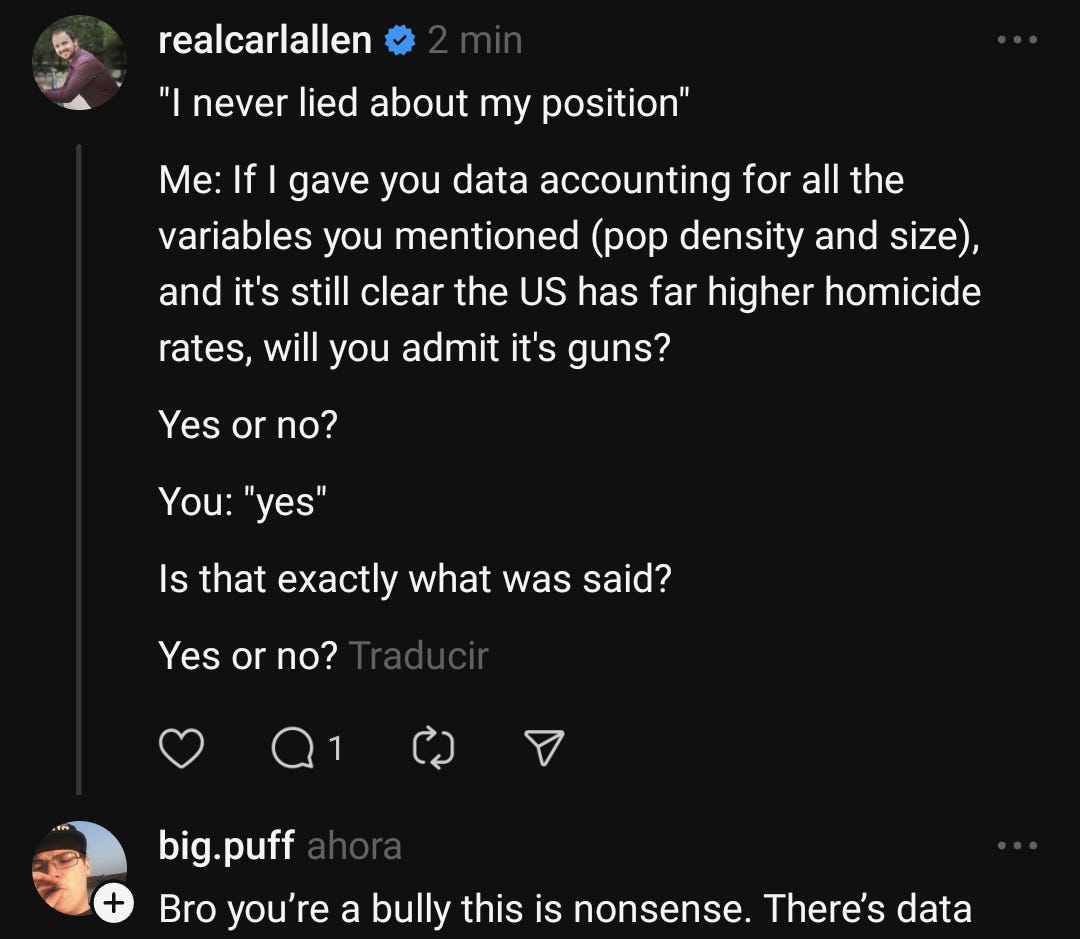

But to my surprise (after only one attempt to change the subject and refusing to answer the question) this guy said “yes.”

I provided him with the chart below, with the following explanation:

These US States have lower population densities and smaller populations than every other country listed. With the exception of Portugal and Japan, every US state listed has less diversity than all the countries listed.

Me: “Now, I have accounted for all the variables you asked, and the US is still a major outlier. Admit it's the guns, like you said you would.”

Him: “Bro you're a bully.”

Pretty typical ego-protection here.

It's true. In debates of facts people who have a strong grasp of them will “bully” those who don't. It's not personal, though that's how they take it - because that's the basis of their beliefs in the first place.

It's not population density, it's not population size, it's not homogeneity of the population - all of which are seemingly reasonable excuses for why “it's not the guns.”

The data doesn't back that up. Despite claiming he was willing to admit he was wrong if proven as such, he never did.

Now, I know you're thinking that “big puff” is not exactly the pinnacle of qualifications here.

I only use him as an example because he's the most recent one who can string sentences together and appears to be a real person. But anyone who has ever engaged on any topic understands that his demeanor is highly representative of people who hold irrational beliefs and factually incorrect positions.

Why engage with these people?

I debate random people on the internet for the same reason professional baseball players take batting practice.

Believe it or not, just like soft-tossing a ball to a Major League hitter helps them develop or refine skills to hit 100mph fastballs and 90mph sliders, occasionally I'll find value in these interactions.

The list of people I've debated (formally or informally) who are qualified, or even experts, is not short.

And as I've learned over the years, even people who are considered experts in their field, do not debate much better than this.

So I guess it's less like batting practice for hitting 100mph fastballs than it is for hitting 60mph ones.

But practice is practice.

Accounting for confounding variables is, not to brag (but also to brag) something I'm pretty good at.

Like most things in the world, complex phenomena are not easily or solely explainable by any one factor.

But easy access to guns is, by far, the largest contributor to homicide rates (and death rates, because suicide is also bad) in developed countries

This is not a position I have held my entire life. Despite being pretty progressive in most of my views, I still believed more guns = more safety for a good part of it.

It's not that I think this position has no merit, it's that this hypothesis of more guns = less crime is being tested in the real world and it just doesn't hold up.

Now, are guns the only factor that contributes to homicides?

No.

Often in this discussion, gun maximalists will try desperately to argue with this strawman. Do not allow it for a second.

There are lots of factors that contribute to homicides. Is easy access to guns high among them, or the primary one?

That's the debate. It's not a long one.

This is the same “confounding variable” argument people had about lung cancer in the 1950s:

Just because smoking wasn't the only contributor doesn't mean it's not dangerous. Life isn't that simple.

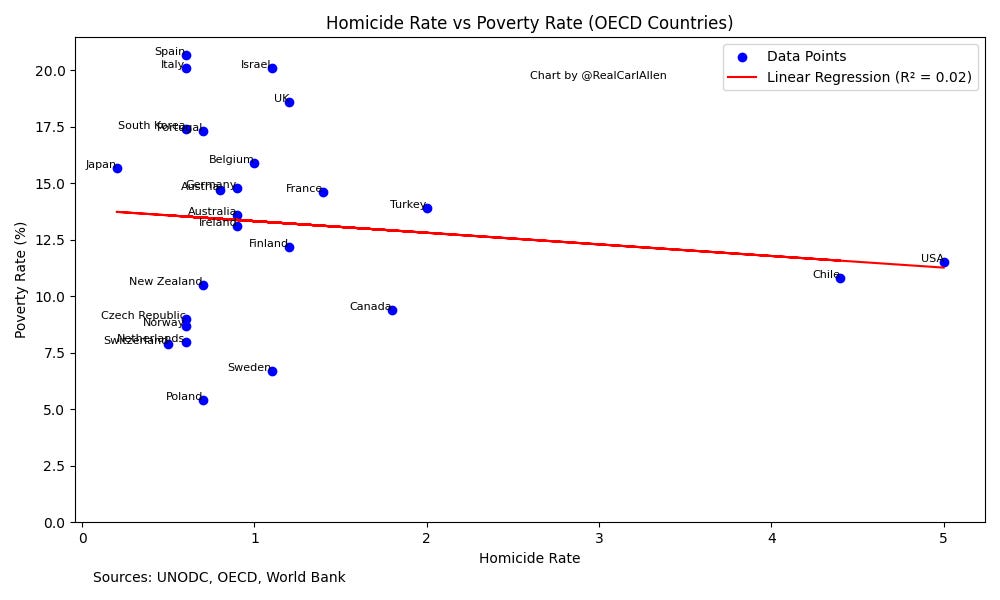

Aside from events like war or terrorism, and setting aside gun ownership for the moment, poverty seems to be the largest contributor to homicides.

Here is the poverty rate vs. homicide rate for the 50 largest countries. Why 50? You can probably guess where I'm going.

Wealth explains a fair amount of the homicide rate: wealthier countries tend to have less murder. Fair enough.

But like any real-world data set, there are outliers.

Those outliers do not negate the trend.

In fact, the US looks quite favorable here! That is, if you compare our homicide rate to countries like Nigeria, Sudan, Brazil, Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Venezuela.

But factors like war and government instability can easily contribute to homicide rates…and that's hopefully not something US citizens will be in a position of similarity to anytime soon.

Once you compare the US to its more closely-related peers (wealthy democracies with a history of stability) things become less favorable for US numbers.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international organization of 38 countries that promotes economic and societal development.

That is, this is a selected (e.g. nonrandom) group of generally wealthy, stable, developed countries.

My hypothesis was that poverty no longer offers any potential explanatory connection to homicide rate, largely (if not entirely) because we've artificially selected countries that do not have notable rates of poverty, among other things.

At least that was my hypothesis. More on that soon.

But watch what happens when we account for gun ownership:

This is a remarkably strong relationship. The only countries that don't fit pretty well into the relationship are Chile, Turkey, and the US.

Skeptics of the gun-to-homicide rate are quick to point out the exceptions - in this case, Chile.

Of course, if Chile fit perfectly on the trend line, there would be some other excuse, for reasons I've explained previously.

But just to hammer home my point that the deniers have no rational reason to deny the reality of the relationship:

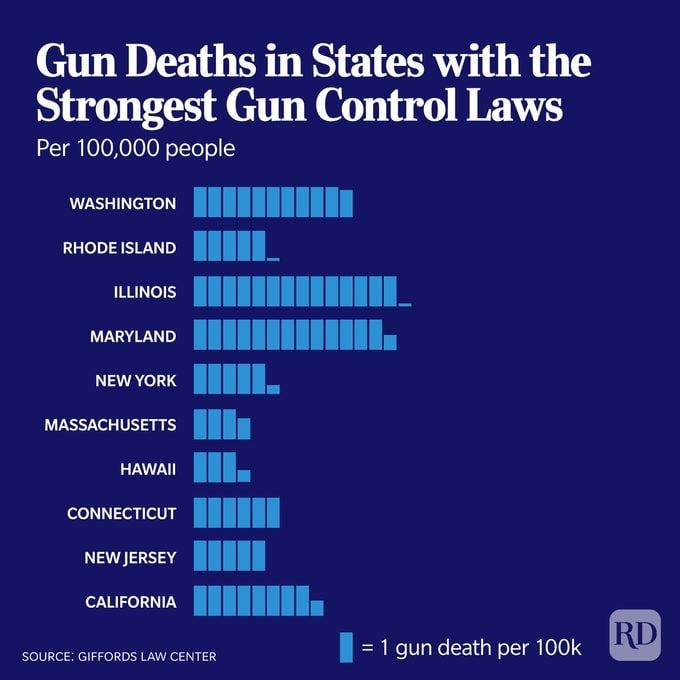

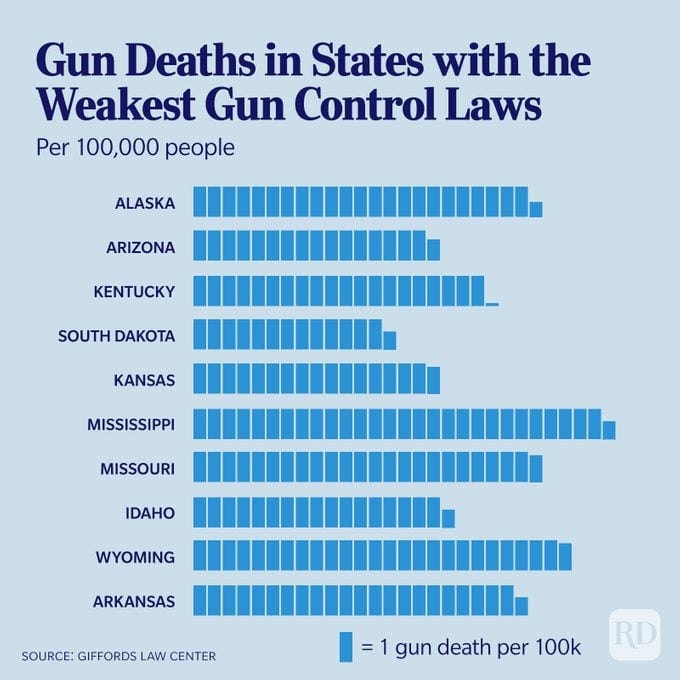

The states in red have more guns and more firearm deaths than the national average. There are many of these. They are almost exclusively the ones with loose gun laws.

If guns make these people safer, people in these states shouldn't be dying from guns so much.

The states in blue are the ones with above average gun ownership rates but below average gun mortality rates. If guns made us safer, this would be the norm.

And yet, it's reserved for a few states with stricter gun laws, and/or a very sparse population. Achieving this status varies year-to-year, because the difference of just a few gun deaths in a small state can push them above or below the national average.

The only states consistently on the good side of this line is are Vermont, New Hampshire, and Oregon.

It's true that stronger gun control laws aren't a magical way (I didn't say magic bullet) to eliminate all homicide.

But again, this strawman tests the category of the Nirvana fallacy: arguing that since some proposal isn't perfect, and won't solve everything, it's not good enough?

On this subject, you'll see this fallacy employed when people try to bring up the fact that other countries still have homicide - with weapons like knives.

The proper response is:

“So?”

It's not a valid argument. If a country has a tenth of the homicides, that's a good thing, actually.

It’s like if someone in poverty who played the lottery everyday were offered a comfortable, salaried job said:

“Why should I work hard, take this good job, and invest what I earn…I'll never be a billionaire that way.”

The alternative to living in poverty isn't becoming a billionaire.

The alternative to high homicide rates isn't zero homicide.

More guns, and easier access to them, clearly isn't solving the problem:

Population density does play a role. States with easy access to guns AND large cities tend to fare poorly.

The biggest surprise to me, there's a very strong relationship between poverty and homicide rate in the US.

Next to better gun laws, decreasing poverty would do more to reduce the homicide rate than anything else I could find.

That's an indirect way to solve the problem, but all good solutions are multifaceted.

I suppose a good politician could run on this reality and make a dent in numbers simply by decreasing poverty.

But make no mistake about it -

You can account for whatever potentially confounding variables you want, and compare any US State to other countries, you'll find the same thing.

It's the guns.

If someone wants to argue that a higher number of homicides is acceptable for this freedom to own the coolest boom boom machines, they can.

If they want to argue that the higher number of accidental deaths, suicides, and mass shootings is a fair tradeoff for some perceived “self defense” then that's fine too.

But that's where the debate starts. There's no debate that more guns and easier access to guns makes a population less safe.