It might sound hard to believe, but we're living through scientific history, and you're in the middle of it.

The belief that polls are predictions of election outcomes, and that the “margin," “spread,” or “lead” someone has in a poll or poll average should - if accurate - translate to a victory by that same margin is junk science.

This belief relies on the assumptions that no one changes their mind close to the election, and that undecided voters always split evenly to the major candidates.

This “margin” model is as bad for analyzing poll data as the geocentric model was for studying stars and planets.

Nonetheless, this geocentric idea of what the “poll spread” means has sustained for 100 years and counting.

It remains the consensus belief of (to my knowledge) every analyst and professional organization around the world.

And I plan to put a stop to it.

In my book, I use the analogy of “smoking and lung cancer” to make a very important point:

If the experts in a field misinform the public about scientific facts, then the public will have no chance to understand that it's wrong.

That leads to two possibilities:

The experts don't know they're wrong

The experts don't care they're wrong

If the experts don't know they're misinforming the public, that says a lot about their expertise.

If they don't care they're misinforming the public, that's probably worse than simply being wrong.

And herein lies the conflict of interest:

If your perceived expertise (or job) in a field relies on something that might not be true being true (say, the belief that smoking isn't bad for your health) then you have a huge incentive to not research it.

More problematically, you have a huge incentive to suppress, dismiss, or defame people outside your bubble who do want to research it.

Status quo bias dictates that “the way things have always been done” is accepted over anything new - even if the new way is objectively better.

Human psychology is a separate topic.

I prefer to think of it as mental inertia: once an idea has reached some velocity, stopping or reversing it requires a disproportionate amount of effort, compared to if the idea had never moved in the first place.

I recognize the mental inertia I'm up against, and I've been (metaphorically) beaten out of the naivete I had when I started researching this ~8 years ago, when I believed:

“If I show my work clearly, and it disproves the current calculations, then it will be accepted.”

Look away, kids who want to Do Science:

But if you think I'm going to quietly allow unaccountable pseudoquants get away with spreading misinformation, you are mistaken.

Living through history

Geocentricism, the belief that the Earth is the center of the universe, and specifically the Ptolemaic model that said planets and stars revolved around a stationary Earth, is now understood as super obviously wrong.

But could you, reader, disprove it?

In your current capabilities, without access to research done by other scientists, could you independently find enough evidence to support the idea that the Earth is neither stationary nor the center of the universe?

Even with knowledge that the conclusion is wrong, you probably couldn't (and that's okay, most people can't…that's why we do science in the first place).

Indeed, the idea that we're currently spinning at about 1,000 miles per hour on a planet zooming around the sun at 67,000 miles per hour isn't exactly intuitive.

So when someone says “Earth is stationary” that checks out.

But what about the movement of the sun and stars? The moon? Other planets? How can we explain that?

Well, it turns out, in order to preserve the unproven (but intuitive enough) assumption that Earth is stationary, you can do some pretty weird math involving deferents, epicycles and equants that accounts for all of this!

It's really amazing that a belief with a premise that we now know is very incorrect could produce mostly accurate observations.

But this ad hoc math (adjusting numbers to preserve the unproven assumption, once your old math starts to disagree with newer observations) is not a reputable practice.

What ends up happening is that the math becomes increasingly convoluted, because every new observation that disproves the old math requires updating.

Convoluted does not always equal bad, and adjusting your calculations when disproved by observation is a good thing, but it creates some weird problems:

What happens when the new math (let's say, version 2) contradicts what the old math (version 1) had said was true, and then version 3 agrees in some ways with version 1, but directly contradicts version 2?

Repeat.

If your primary motivation (conscious or subconscious) is preserving the belief, there's no problem.

But because the math (again, often contradicting itself) is always changing to adjust to new observations, at no point can almost anyone say how or why the math is wrong. Constantly contradicting what it claimed was correct before is not considered a problem.

The only way to prove the math wrong is to challenge, and disprove, the unchallenged assumption.

For that reason, as an aside, I've concluded that a combination of independence, skepticism, passion, resilience, confidence, tenacity, and resilience are the primary traits necessary for innovation in science.

Intelligence, by whatever metric, is secondary at best. I'd wager any amount of money that lots of more intelligent people have worked in every field than the field's foremost innovators.

Dismissal of a field’s established norms, willingness to question them, and/or attempts to innovate within it is, almost by definition, an arrogant pursuit.

What, you think you're smarter than Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle?!

The belief in geocentricism sustained for over a thousand years.

Ptolemy’s model was basically accepted until Copernicus, Kepler, and others (again, over a thousand years later) dared to challenge this traditionally accepted assumption.

I find this interesting, maybe

or Neil deGrasse Tyson would have more to add.But this is my Substack, dammit, how does this relate to poll data?!

Probability is a weirdly new field

While we think of math as an old field - it is - the branch of probability (which is often as logic-based as it is math-based) is very new.

It wasn't until the 17th century that probability theory was studied, and to this day experts still misunderstand the field's most basic statistic - the margin of error - and apparently no one else cares to correct it (this article was published four years ago, and as of writing, it has not been retracted).

Given the egregious nature of this error, I'll use this as an early gauge as to how long it takes my findings to be accepted.

The Literary Digest, conducting its first polls more than 100 years ago, rose to prominence for their “uncanny” ability to predict the election outcome. Despite their unweighted, biased, and nonrandom samples, the Literary Digest polls (for four Presidential elections in a row) produced accurate predictions.

4/4

100%

Their poll produced accurate predictions, therefore their polls were good. Likewise, I don't feel like I'm moving, therefore the Earth is stationary.

It is/was accepted because it feels intuitive, even if it can be proven wrong.

But you can't prove it wrong if your analysis demands that you assume it to be true.

Today, Literary Digest polls are synonymous with unscientific methods (because, eventually, their poll didn't predict the correct outcome).

Notably, by the field's own definitions, they would have also rated Literary Digest polls extremely highly for accuracy…until they weren't.

Does this ad hoc reasoning sound familiar?

The good news is, at least on the polling side of things more scientific methods replaced them.

The bad news is the logic that polls, if accurate, will predict both the winner and the winner’s margin, hasn't gone anywhere.

“Spread” Geocentricism

In 2012,

rose to fame on the back of - as it was wrongly reported - predicting the outcome in 50/50 states.As forecasters are quick to tell you when their forecasts are seemingly directionally incorrect, and their probabilities are misrepresented as calls (but predictably quiet when that misrepresentation makes them look good) forecasters simply put probabilities on things.

Saying someone is 80% to win a state is not the same as predicting they will. That sentence is accepted as true.

But when I say:

“A poll or poll average stating a candidate is “ahead” is not a prediction they will win, and this cannot be declared as a representation of poll accuracy”

That is extremely controversial - and directly contradicts the “geocentric” polls-as-predictions standard that still exists.

The poll predicted how much someone would win by. That's a verbatim quote from

’s book. And it's the shared belief of the field. And it's wrong.Nonetheless, Silver, like Gallup, deserves credit for improving the field's scientific standards. In Silver's case, taking the field from deterministic (prediction of who will win) to probabilistic (this is the probability my forecast assigns to them winning) was a big step.

Even if this hasn't totally reached the public, it has unquestionably improved things.

Silver's forecast model - like all good forecast models - is designed to try and capture that inherent uncertainty that makes probability intimidating, challenging, and even discomforting.

Not being able to give a direct answer to “so, what will happen?” is - especially in politics - discomforting. But that doesn't mean we should pretend.

From 2022:

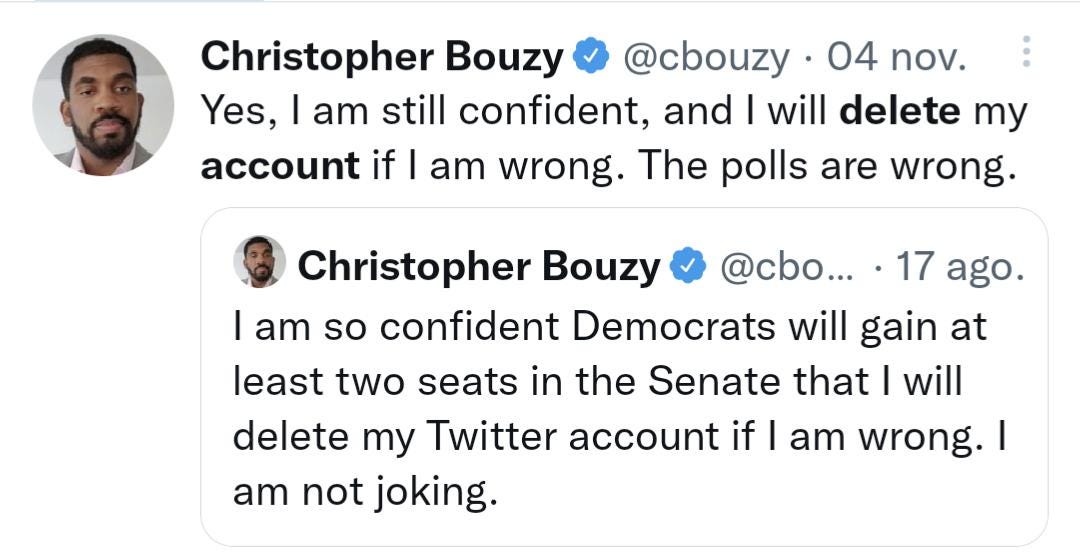

While Sam Wang at least stuck to his word and ate a bug after his terrible 2016 forecast (though blamed the polls for his own inability to quantify uncertainty) Bouzy still has not deleted his account, despite being wrong about how many Senate seats Democrats would gain, and being wrong about his “house projection.” No wait, this one.

By the field's own definitions, if Bouzy’s guess had been right (despite a clear lack of a model, or understanding of probability) it is, therefore, better.

Being right (or the closest to right) means you're the best.

This is literally how they judge poll accuracy.

And if you're not catching the irony here, predictions are at least supposed to be predictions. Polls aren't.

FiveThirtyEight’s ad hoc math

To bring things full circle (sorry, full oblate spheroid) in an attempt to defend their “spread” geocentricism, FiveThirtyEight has taken to some sad - but predictable - revisionism.

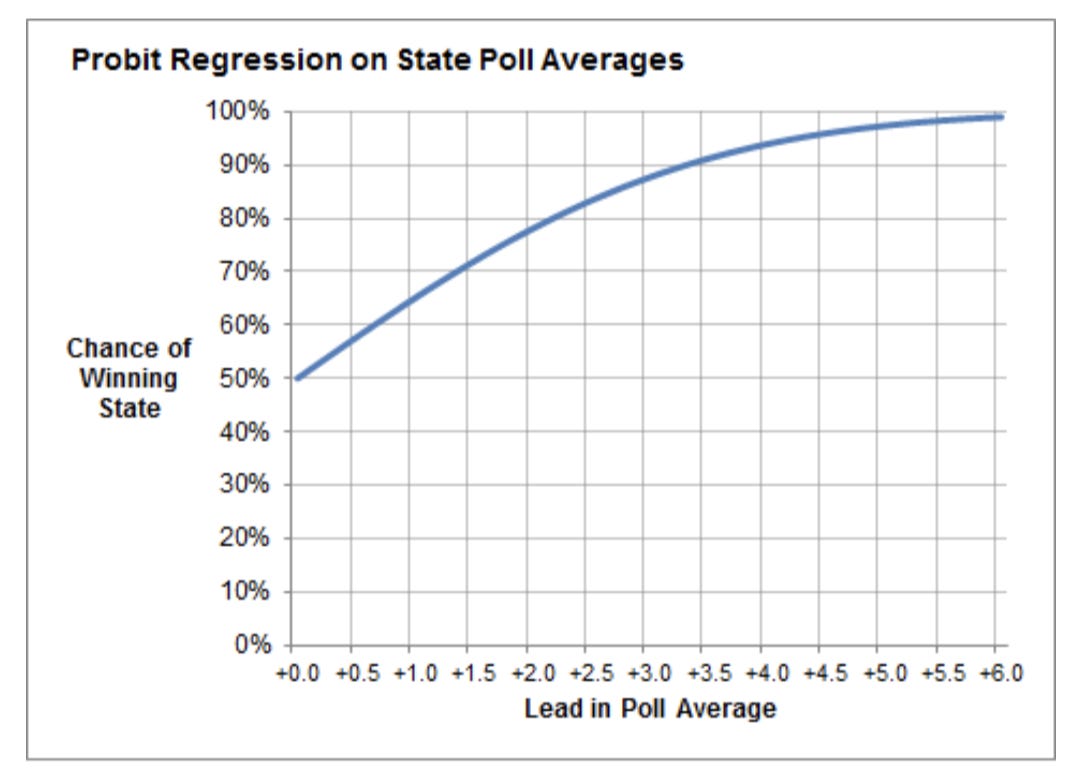

In 2012 - the election that really catapulted Silver to fame - he was adamant that Obama was a strong favorite to win reelection. That sentiment was basically shared, but it's the logic Silver used in that analysis that is most interesting.

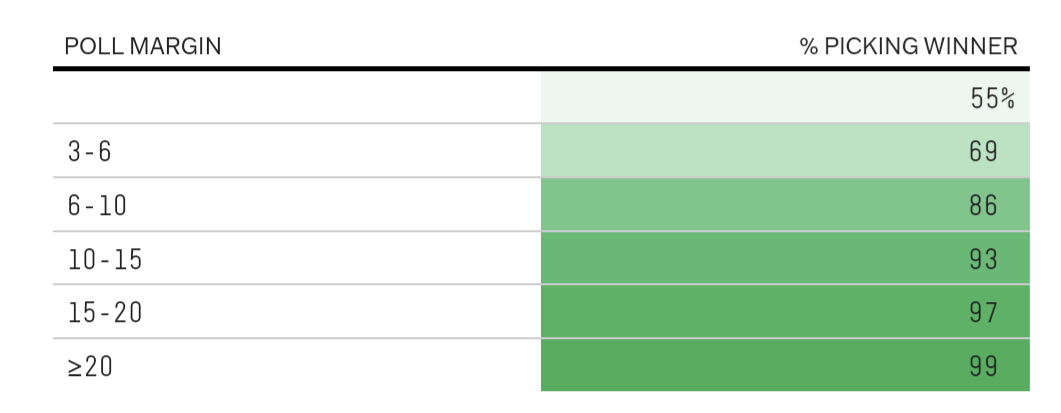

Silver said that a 2.4-point lead in the polling average would translate to an 82% win probability.

Note that the win probability approaches 100% at a lead of 6.

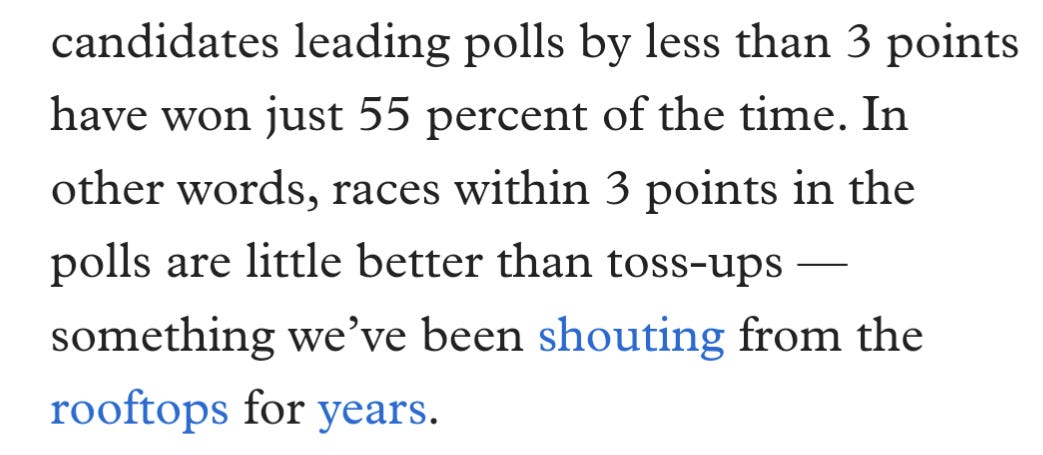

Fast forward to 2023.

Wait a minute.

In 2012, a 2.4-point lead implied a 82% win probability

And by 2023, leads of less than three points are “little better” than a tossup?

I suspect you see what's happening here.

When Bouzy made an overly confident and precise claim, he got really angry that people would dare call him wrong despite being 100% wrong, and he (successfully, according to his many followers) convinced people he deserved credit for being kind of close.

Had he been exactly right, he would have claimed to have known (and most people would've believed him). But even when he's wrong, he simply revises his position so he can still claim he was right. (Lichtman's keys also fall into this category, sorry).

But back to the “math.”

What does a 2.4-point poll lead translate to in terms of win probability again?

2012: about 82%

2023: “little better than tossup”

This is Ptolemaic math. They can add all the epicycles they want, and claim they've “been shouting” whatever revised version of math they're using is the one they've always been using, but until they understand that the Earth isn't stationary, and that spread is a junk metric, they'll never solve any meaningful problems.

They are definitionally incapable of answering the question - whether a lead of this size yields a 55% or 82% win probability - because they're using a spread-centric model.

They've assumed that this is a valid way to look at the data, that it can't possibly be wrong, and when their last round of calculations disagrees with observation…they just ad hoc it.

The answer to the question of: what does a 2.4-point lead in a poll average mean?

It depends how close the leader's poll average is to the finish line. (Among other things).

Their model is spread-centric (how much is the leader up by?), my model is share-centric (what are the actual numbers for each candidate, how many third parties, how many undecideds?).

These models are as different as geocentricism and heliocentrism.

Like heliocentrism, a share-centric model will allow otherwise smart analysts who hadn't previously questioned their field's traditions the freedom to ask (and answer) important questions reliably and form falsifiable predictions, not ad hoc, and lead to a very quick domino effect in which new discoveries fall into place.

And yes, astronerds, I know heliocentrism in its original form was not entirely correct, but this imperfection-but-vast-improvement analogy is kind of what I’m after.

If you want to understand this topic that is not nearly as complex or technical as orbital mechanics, it's in my book.

The link to the incorrect margin of error is dead, and I'm enough of a nerd that I wanted to read it!

If you haven't already read it, I think you might dig the book Fluke by Brian Klaas. In it, he discuses a little of the history of probability science.