Polls are not predictions

And "Predictive" is a misleading term

I'm pretty firmly on the record with my explanations regarding the fact that polls are not predictions of an election result, or election “margin.” The concept isn't necessarily intuitive (a fact I blame on the inundation by experts and media of polls-as-predictions) but it's pretty easy to understand, once you allow your mind the freedom from that falsehood.

A simple way of thinking about the math (though it's nearly a perfect analogy) political polls are blurry snapshots. Or, an imperfect estimate of a present state.

Even a perfectly clear snapshot of competitors in a footrace showing someone is ahead isn't a prediction they will win. Imagine, looking at a picture and declaring its accuracy according to something that happened later. Who would do that?

Of course, a runner pictured ahead at some point before the finish line, who doesn't eventually win, doesn't mean the picture was wrong (and, therefore, the photographer messed up) - but that's exactly how polls are treated! No exaggeration.

Worse, there's no such thing as a perfect snapshot in poll data (all polls have a margin of error and other potential sources of error) so in a blurry snapshot, you can almost never even say for certain who is ahead!

(This gets into the misplaced and unscientific obsession for a poll and forecast accuracy to be measured according to whether they are “directionally correct” which I also discuss in my book).

Somewhat technically speaking, the math that underlies the “survey” instrument - the math from which poll data finds its value - infers the present state of some population by taking random sample(s) from it.

That's literally what the margin of error refers to - the most basic statistic of the field.

Some experts don't even know how the margin of error works.

Here, this expert applies the margin of error of the poll to the result of the election, and claims it proves polls aren't as accurate as the 95% confidence interval claims:

No, Cal Berkeley Ph.D, that's not how the margin of error works.

A poll that says “56% +/- 3%” does not “predict” that candidate will FINISH between 53% and 59%.

Do I need to do another rant about undecided voters?

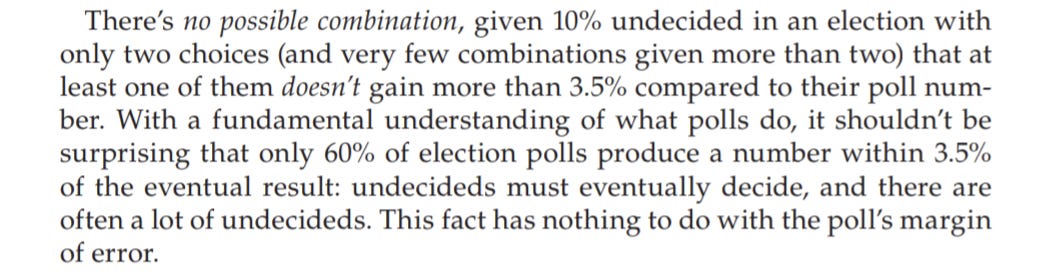

There are many flaws with this math. In my book, I demonstrate the most obvious flaw with it:

Misunderstanding the most basic statistic of the field does not inspire my confidence that this issues are understood, or will be fixed without me stirring up some shit kindly demonstrating the flaws.

This fact that the margin of error given by a poll does not apply to some future value, while seemingly obvious enough that most non-experts can understand it (if not before explanation, certainly after), is plainly not understood by many (possibly any) of the field's most prominent experts.

G Elliott Morris, in his book, incorrectly saying what a poll “predicted”

Nate Silver, contrary to what you may perceive of my opinion of him, is probably one of the best in the field, but also gets this basic scientific fact wrong:

He thinks polls and poll averages are supposed to predict the electoral margin of victory. That's not correct.

But maybe these guys with their incentive for clicks and simplified explanation just use unscientific generalizations for ease?

(This is, unfortunately, the most frequent form of apologetics I hear when people defend alleged experts being verifiably wrong about a simple statistical fact. Which led me to write an article entitled them don't understand polls).

To put it simply, anyone who says, implies, or otherwise assumes that “the polls predicted…” anything (and doesn't correct themselves) does not understand what poll data means.

It's not shorthand, it's not an estimate or a simplification, it's just wrong.

But hey, let's give those guys the benefit of the doubt. Let's pretend their words don't count, what they write in books and technical explanations of their analysis doesn't count, and just grant the unproven (and disproven) assumption they do know polls aren't predictions.

Let's then just look at academic journals: written by experts, for experts. Can we make excuses for them doing it?

Here is a selection of quotes extracted from one research paper, put together by a panel of experts for the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR):

There were dozens more instances of them implying what “polls predicted” so to avoid the debating the tedious, goalpost-moving excuses about what they really meant, them being directly wrong should make my point:

Them don't understand it.

(Other countries are even worse, if you could believe it, I'll spare you the citations and just talk about the US for now).

So the question is…what do we do about it?

My impetus for writing a book stems from nothing more than my belief that science should strive to improve its knowledge, understanding, and ultimately be more correct than it was in the past.

The statement that “poll data provides an estimate of a simultaneous census” probably doesn't mean much to you without the context of the book - this is presented about halfway through after some explanation and examples - but it represents the scientific replacement to the current, incorrect, “polls predict…” standard.

In the book, I don't just show the current analysis is wrong, I provide a basis for a correct one. After that base of understanding is shared, political polls are analyzed - past, present, and future.

Whether my contributions are perceived as substantial or minor, I'm not really concerned. What I am concerned with, is that they go without consideration for some period of time, and the improvements they would inevitably lead to are delayed or lost.

Acceptance of my work is complicated by the fact that I'm not an authority in this field. Hell, before 2020 I was barely in this field at all. I'm fighting a very uphill battle just to be heard (let alone understood). That's fine! It makes plenty of sense that an “authority” has more reach with their work - for better or worse.

But at some point, a legitimate scientific field will have to consider the reality that their view of “polls predict…” is not correct and that there is a better way. People whose work I prove to be poor have a lot of incentive not to discuss it, after all.

Polls aren't predictions

Okay, you get this part.

A poll that says:

Candidate A 46%

Candidate B 44%

Undecided 10%

Doesn't “predict” anything about the final result.

It doesn't predict that Candidate A will win, not even that Candidate A “should win” nor that Candidate A will “win by 2” (all verbatim examples of how experts wrongly interpret poll accuracy).

For one, each of those numbers comes with a margin of error. All of them - including the number of undecideds - could be higher or lower than the number reported on the “topline.”

But higher or lower compared to what?

Remember, that margin of error doesn't apply to the future. It only applies to the population at the time the poll was taken.

It says that if you followed this poll’s methodology and had conducted a census at the time the poll was taken (instead of taking a sample from it) each value should fall within the margin of error as often as the confidence interval specifies.

(This is where you say: ah! a simultaneous census!)

The math isn't quite that simple (we have to differentiate between ideal polls and nonideal ones) but the underlying concept, like all good science, is testable, tested, and proven.

The book of course expands on all of these concepts, and encourages readers to challenge my findings, because my desire for science to be accurate is greater than my ego's desire to be right. (But I'm right)

I have no doubt, however, that my findings can be built upon.

Regardless, it's easily shown that polls are not predictions: the tool itself makes estimates of a present state, not a prediction (nor even an estimate) of some future one.

Are polls predictive?

This is where the desire to convey complex meaning in simple terms bothers me.

The question of “are polls predictions of the election result” is easy: no.

But predictive? That's harder to explain.

Let me demonstrate with another simple (and accurate) analogy:

What does a scale measure?

Well, it measures force exerted on it, but we don't need to be technical or overly precise for this analogy. It works the same to say it simply:

It measures weight.

Got it.

“Scales can measure body weight” is true.

A scale is a tool with a specific purpose - if I stand on it, it should tell me my weight.

Like we can differentiate between ideal and nonideal polls, so too can we differentiate between ideal and nonideal use of a scale (e.g. that the scale is used according to its instructions for giving the most accurate reading…not on carpet, etc.)

Let's say I know how a scale works and I use it appropriately - what I'd define as “ideal” circumstances.

So, here's the question:

Is the number given by the scale a prediction of my weight next week, next month, or next year?

Most people would say: lol no, of course not.

(Congrats, you understand poll data better than experts).

For what it's worth, scales also have a margin of error, and that number also only applies to the “simultaneous” present value - not some future one.

And if you don't understand what the margin of error means, you'll probably find that taking your weight days or weeks apart will probably often produce results “outside the margin of error.”

The follow up question though:

Is a scale predictive of your future weight?

To which the answer is…sigh…kind of?

The problem isn't using a scale to inform a prediction of someone's future weight. That's a very logical thing to do.

The problem is treating the retrospective accuracy of the scale’s past measurement by how closely it predicted some future value…something we already agreed it can't and doesn't try to do.

There's a reason this is my “banner.”

So let's talk through this “predictive” thing.

You, reader, probably have no idea what I weigh.

So, if tasked with guessing what I will weigh on November 6, 2024, you'd basically be guessing. At best, you'd look at some pictures and work from there.

November 6 isn't a long time away, but certainly long enough for some weight change - how are you going to make your guess?

Are you going to assume:

Your estimate of my current weight + a little

Your estimate of my current weight - a little

Your estimate of my current weight, unchanged

Here, you're relying on what I'd call the “fundamentals.” No scale data, just some loose knowledge of what people who look a certain way might weigh - you might even use some generic average of adult US men.

Now, there's nothing wrong with estimating someone's weight from a photo (given that it's done for a contest with their consent haha)

But of course, you'd rather have the result from a scale - or scales - to give you my weight.

Now, given some scale data, what do you do?

Consider only your estimate of my weight by looking at photos

Consider only the scale's provided data

Assign “weights” to those values and use both

Most people, given the relative accuracy of scale data, would basically throw out their estimate based on looking at photos. No problem.

(No, poll data isn't as accurate as scale data, don't think beyond the analogy right now!)

I just want you to predict my election day weight. This weight will be measured by some super-precise instrument that can't be wrong.

Now, with some scale data, you have a number you can be reasonably certain is an accurate representation of my body weight.

But accurate compared to what?

Accurate compared to right now. More specifically, the moment the measurement was taken.

Nothing to do with November 6th.

Now, you're left with the same problem as you had when you had no scale data!

All you have is a more precise estimate of my current weight!

So, what are you going to assume for my future, election day weight?

The scale’s estimate of my current weight + a little

The scale’s estimate of my current weight - a little

The scale’s estimate of my current weight, unchanged

The problem, even with objectively better data, hasn't changed. You still have to assume, project, or otherwise forecast some future value. All that has changed is the amount of confidence in the range of possible and likely outcomes.

Your ability to make the correct assumption about my future weight is independent of the accuracy of the scale - whose only job is to measure my present weight.

(The quality of a forecast is independent of the quality of the poll data used to inform it).

I'm sure you can come up with convincing arguments for any of those gain, lose, or “no change” weight assumptions.

So… here's the question:

Understanding that the scale isn't supposed to be a prediction of future weight…

Which assumption do you use to measure how PREDICTIVE the scale was?

You have to use one!

If you assume weight change over the course of 10 weeks should be approximately zero (a reasonable assumption) you'd grade pollsters who were objectively wrong (but in the right direction) about my weight 10 weeks ago as being more accurate.

For example:

In the event I actually gain a little weight in that time - but your assumption is that it won't change - a pollster (or scalester) whose methods consistently overestimate weight by just 2% will be viewed as more accurate than those who got my weight right 10 weeks ago!

See the problem?

(You can see why I propose the simultaneous census standard for judging accuracy)

Is that scalester who overestimated my weight in a year I happened to gain weight more predictive than others if we do the same contest next year?

Probably not.

But maybe, given this data, you change your default assumption. Maybe the assumption that weight will stay the same is the wrong assumption. People (especially men my age) tend to gain a little weight over time, after all. So, with that “historical trend” being what it is - maybe the best assumption is that I gain a little weight.

Now, we have the opposite problem. In the event I lose some weight, even just a little, the assumption that weight should go up over 10 weeks has created another scenario where inaccurate scalesters would be graded as accurate:

Those who dramatically understated my true weight at the time of the measurement will be viewed as more accurate.

(If they report 5 pounds under my true weight, and I actually lose 3 pounds, if you incorporate the “gain a little weight” assumption, being 5 pounds under 10 weeks ago appears right…despite having been wrong, by the proper “simultaneous census” standard.

So the question of “are polls predictive?” Like “are scales predictive?” isn't a simple question.

How you grade their predictiveness requires making assumptions that are not related to the tool's accuracy.

In many elections, undecideds split about evenly, and in many elections, they do not.

In many cases, 30-something year old men will not gain or lose weight over a 10 week period. In many cases they will.

How we interpret the predictiveness of a tool that is not intended to be predictive, still requires making assumptions that are irrelevant to the tool's accuracy.

Your calculation now incorporates what you believe to be the most reasonable assumption - which may or may not be - but even that most reasonable assumption can't (if we're doing good science) be assumed to always be true.

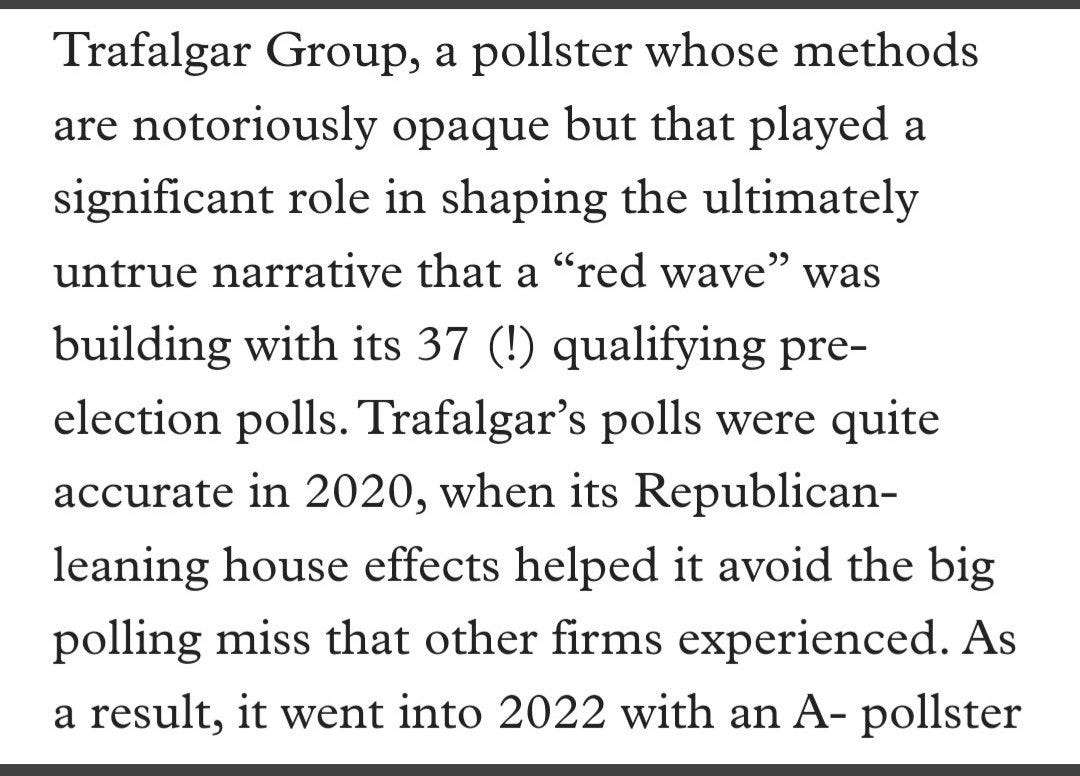

This is why the pollster grading is well-meaning but misplaced. The method employed by Silver, FiveThirtyEight, and (to my knowledge) literally everyone in the field besides myself grades pollsters partially or entirely by how “accurate” they were (if you incorporate the assumption undecideds split 50-50 and no one changed their mind within three weeks of the election, which we know is never true, but they use it anyways):

“Past performance predicts future performance” is also not scientific, even if it might be the most reasonable one.

I'll take a transparent pollster with good methodology who has never conducted a poll before over one who is “opaque” but has gotten lucky with their reported (possibly fabricated) poll data in the most recent past.

They went from “C” in 2016 to “A-” in 2022 because of their “accuracy” in 2018 and/or 2020.

That's garbage.

So to answer the question, “are polls predictive?”

It's not that simple.

Is poll data “usable or valuable for” prediction? Yes.

The way I put it is that poll data can inform predictions.

But is poll data “based on or generated by using methods of prediction”? No, absolutely not.

I know it's boring, tedious, and it doesn't fit neatly in a headline

(see that linked article for a debate with an “expert” who really didn't like that I was trying to get him to define a word like “accuracy”)

But the word “predictive” has an imprecise meaning that can easily be misinterpreted, especially among people who aren't interested/informed enough to read a whole article on the subject.

To say “predictive, not prediction” is true, but only for a specific definition of the word predictive…and this drastically understates the magnitude of difference.

The fact that literal experts say, write, and publish “the polls predicted” in their work is not just evidence - but proof - they don't understand them. And for that reason, outside of circles of people who I know have read my work or been forced through this interaction with me, I prefer to not use the term “predictive” at all, because this topic is clearly not well understood.

“It is reasonable/valid/good to use poll data to help inform a prediction” is probably as close as I'll get.